Part One: Plagiarism and the Power of Travel

Note: Part Two, “The Otomi Tenangos”

Cultural appropriation is a loaded and complex concept we often come across. Given the power of social media, much discussion is generated, especially when a new case of a designer or other outlet, integrates elements deemed to be cultural patrimony into their designs. Global influence on the world of fashion is not new, and in some ways should come as no surprise, given the beauty and depth of material culture in dress and textiles from many countries. Cuisine too has been adopted in cultures they don’t come from. For this, we are enriched and are lucky!

Some definition of the term/concept of Cultural Appropriation here: From Wikipedia:

“Cultural appropriation is a concept dealing with the adoption of the elements of a minority culture by members of the dominant culture. It is distinguished from equal cultural exchange due to the presence of a colonial element and imbalance of power. Particularly in the 21st century, cultural appropriation is often portrayed as harmful in contemporary cultures, and is claimed to be a violation of the collective intellectual property rights of the originating, minority cultures, notably indigenous cultures and those living under colonial rule. Often unavoidable when multiple cultures come together, cultural appropriation can include using other cultures’ cultural and religious traditions, fashion, symbols, language, and songs.

Some writers on the topic note that the concept is often misunderstood by the general public, and that charges of “cultural appropriation” are at times misapplied to situations that don’t accurately fit, such as eating food from a variety of cultures, or learning about different cultures.The term remains controversial. Commentators who criticize the concept say that the act of cultural appropriation does not meaningfully constitute a social harm, and that the term lacks conceptual coherence. Some maintain the use of the term appropriated is unnecessarily loaded, and that the term unfairly demonizes well-meaning people who have been labelled as “cultural appropriators”.

Cultural appropriation can involve the use of ideas, symbols, artifacts, or other aspects of human-made visual or non-visual culture. Anthropologists study the various processes of cultural borrowing, “appropriation,” and cultural exchange (which includes art and urbanism), as part of cultural evolution and contact between different cultures.

As a concept that is controversial in its applications, the propriety of cultural appropriation has been the subject of much debate. Opponents of cultural appropriation view many instances as wrongful appropriation when the subject culture is a minority culture or is subordinated in social, political, economic, or military status to the dominant culture or when there are other issues involved, such as a history of ethnic or racial conflict. This is often seen in cultural outsiders’ use of an oppressed culture’s symbols or other cultural elements, such as music, dance, spiritual ceremonies, modes of dress, speech, and social behavior, notably when these elements are trivialized and used for fashion, rather than respected within their original cultural context. Opponents view the issues of colonialism, context, and the difference between appropriation and mutual exchange as central to analyzing cultural appropriation. They argue that mutual exchange happens on an “even playing field”, whereas appropriation involves pieces of an oppressed culture being taken out of context by a people who have historically oppressed those they are taking from, and who lack the cultural context to properly understand, respect, or utilize these elements.”

Summary:

We can see that the concept of Cultural Appropriation is complex. Cultures and societies have traded, been influenced by, evolved, borrowed and adopted, since the beginning of time. Each case needs to be considered for intent, power relationships, economics, respect, among many other facets. This leads to a less ambiguous and more tangible concept: plagiarism.

From: Plagiarism.org

“Many people think of plagiarism as copying another’s work or borrowing someone else’s original ideas. But terms like “copying” and “borrowing” can disguise the seriousness of the offense:

According to the Merriam-Webster online dictionary, to “plagiarize” means:

In other words, plagiarism is an act of fraud. It involves both stealing someone else’s work and lying about it afterward.”

Once we recognize plagiarism, we can ask, “Why does it matter?” Who gets hurt, who benefits, who loses, why is it wrong and why is it a problem?” There are numerous reasons why plagiarism matters and why it is a good idea to be able to recognize it. Recognition can help inform our actions, decisions, purchases, denouncing rip-offs, and showing respect for a people and culture. If we recognize that a community or ethnic group is being copied by a large corporation, designer, etc., we can choose to not purchase these items, even though they look very appealing and beautiful. These looks do not exist in a vacuum or come from no-where. They are informed by world cultures. This is where “influence” vs. copying become relevant and important. In the case of Mexico, a culture that is steeped in creative expression, rich in cultural and ethnographic iconography, designs are often copied. There are well-known cases, such as the following:

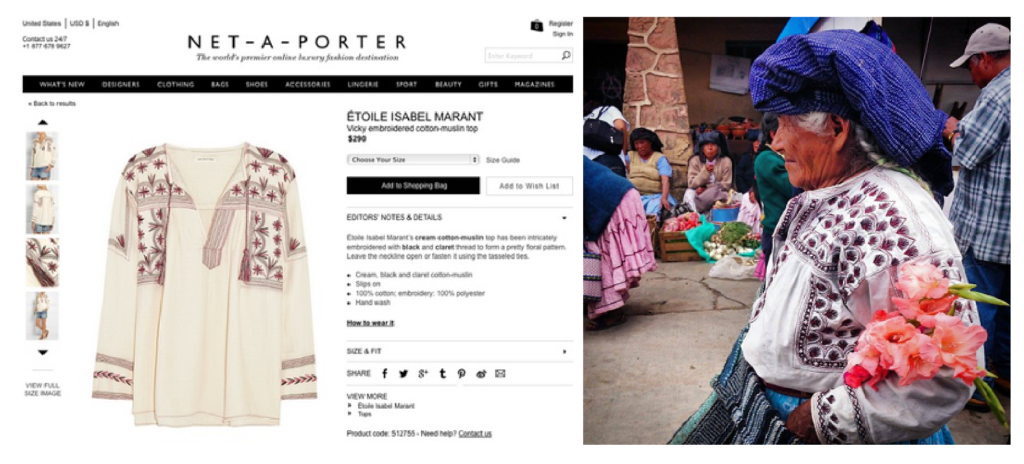

The Case of Tlahuitoltepec, Oaxaca:

A very public and flagrant case, brought to light by singer, now Senator Susana Harp, was the copy of the Santa Maria Tlahuitoltepec (Tlahui) blouse design and style, by a French designer. Harp, on a visit to Texas, entered a high-end department store and was shocked to see what looked just like the “Tlahui” blusa on the racks. She recognized it because she’s from Oaxaca. She posted it to social media, it went viral, and became the “case” for blatant plagiarism of specific cultural expressions by the fashion world. As the Mixe people were not mentioned, recognized, or remunerated from the “ripped-off” design, there was an outcry and a series of legal actions initiated by the community to protect their design.

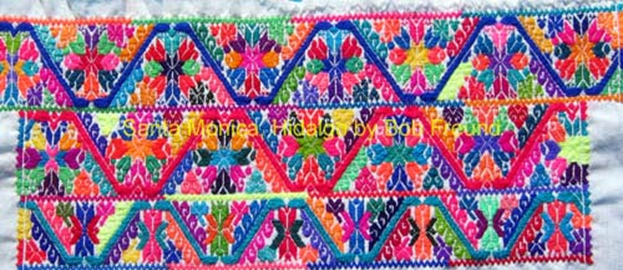

The Case of San Juan Bautista Tlacoatzintepec, Oaxaca:

Clothing Brand Intropia

The Chinantec women from San Juan Bautista Tlacoatzintepec:

The Case of Anthropologie and Pottery Barn (and MANY others), copying traditional Otomi Designs:

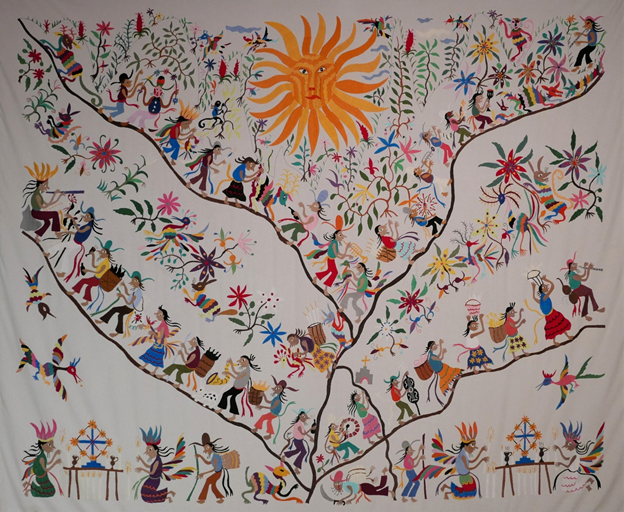

Perhaps no design of Mexico has been more plagiarized than the Otomi designs from the Sierra Oriental of Hidalgo, known as “Tenangos”. These designs are well known for their beautiful embroidery of flowers, people and animals, believed to be inspired by the shaman (curanderos) from the communities. Given the charm of these drawings and embroideries, they are ideal targets for imitation. Printed dresses from Anthropologie (a big and habitual offender), and “Made in China” pillows in “Otomi Designs” were being sold in Pottery Barn. (given public pressure, they were taken off the shelves). These designs are seen printed on plates, dishes, table cloths, and on and on and on.

Since the case of the Otomi designs of the famed “Tenangos” has been and is SO flagrant and prolific, I thought I’d write some information on the original Tenangos. Blog Part Two (see below)

Authentic Otomi

Designer/Copies

While we cannot and should not travel NOW, travel provides curious travelers the opportunity to visit first-hand, meet the weavers, embroiderers, authors of the works, designs, dress, being copied. It offers the opportunity to experience and absorb the cultural and natural context of place and people. Following these intercultural visits, travelers are better equipped, having a greater ability to recognize original creators, their designs and iconography. Knowing the original, helps contribute to recognizing the imitation. Furthermore, the original is always better than the fake. It looks better, feels better and it means so much more, having travelled to the cultural and natural environment, in the homes, workshops of the artisans. Why would anyone want a copy vs. the opportunity to see, admire, learn about and purchase the real thing?

Creating cultural understanding, friendships, deeply admiring the creative energy and artistic talent of people around the world, is a big part of cultural and sustainable travel.

Part Two: Otomi “Tenangos”: Flowers, birds, animals and stories

The term “tenango” comes from the town, Tenango de Doria, located in the Sierra Madre Oriental mountains of Hidalgo. This region of Hidalgo is home to one of the branches of Otomi people, known as the Eastern Otomi, or Ñah-ñu. They live in the mountainous region where Hidalgo, Puebla and Veracruz meet, sometimes called the Sierra Norte de Puebla. It is this group of Otomi who create and are known for tenango embroideries.

These charming embroideries of birds, flowers, animals and “stories” are often seen in places such as, the Bazaar Sabado, La Ciudadela and Fonart Stores in Mexico City. This very specific style and textile art emerged in the 1960’s as a response to severe drought that put the region in a precarious and vulnerable condition. The people here traditionally relied on small scale and subsistence agriculture.

How did they start?

Given the drought, the community sought new ways to generate income. Considering their knowledge of embroidery, it occurred to them to sell their beautiful blusas in the market. Given the amount of time and material that goes into making each blusa, this proved unsuccessful, as they couldn’t get the money out of it, to make it worthwhile. The need was great, so they continued the search, and in the town of San Nicolas, it is said that a woman, Josefina Jose Tavera (who sadly just passed away), came up with the idea to make smaller, less expensive manta embroideries to sell in the market in nearby San Pablito Pahuatlan, Puebla. Her daughter took them to the market and to her daughter’s surprise (she was doubtful anyone would want them), they sold! With this, they started to make and sell more. This caused a stir in the community, and others wanted to get involved. Soon, Josefina was teaching others to draw (dibujar or pintar) and / or embroider.

This is how it started. A new or adapted form of embroidery based on previous knowledge of embroidery techniques used to make their own blusas, was created.

And, what started as a local sale in Pahuatlan, became regional, moving to Hidalgo, then national to Mexico City and beyond, and now, international. Today, these embroideries, that started out as a family enterprise, have become an important part of regional Otomi identity and source of family and community income.

The Otomi people were among the earliest cultures of Mesoamerica, inhabiting the Central Plateau of Mexico. They were later displaced by the Aztec, and today the Otomi are distributed throughout Central Mexico, with most living in Hidalgo, representing the second largest ethnic group there. The Otomi of Hidalgo, live in two primary regions and speak different dialects: one in the Valle del Mezquital in western Hidalgo and the other in the Sierra Oriental mountains on the eastern side. The Otomi live in other regions of Mexico too, including, Ixtenco, Tlaxcala, regions of Michaocan, the State of Mexico, Queretaro, Puebla, Veracruz, San Luis Potosi and Guanajuato. The Otomi are not a homogeneous group. Not only do they live in various States of Mexico, they speak one of nine variants of Otomi.

Rituals and Beliefs

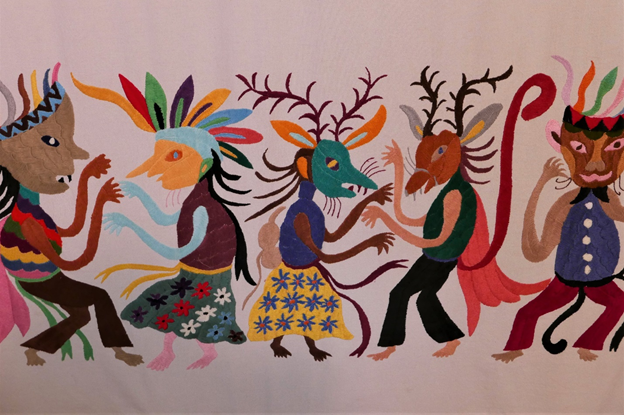

Otomi communities of the Sierra Oriental have a long legacy of traditional beliefs and customs. Rituals establish harmony and order in the universe; in the natural and human world. A pantheon of gods and spirits guide them in all aspects of their lives, including, agricultural cycles, family events (birth, marriage, death), neighbor disputes, illness. In one community, San Pablito Pahuatlan, Puebla, the shaman, or “curanderos” use beautiful paper cut outs from handmade amate paper to represent and manipulate these forces and spirts. They conduct cleansings, healings and ritual ceremonies to protect the villagers. These figures are representations of these spirits.

Paper Cut Outs

According to Elena Vazquez y de los Santos, in her book Los Tenangos: Mitos y Ritos, she tells us:

The curanderos, healers, shaman, have supernatural powers they inherit from their ancestors. They are intermediaries between man, deities and ancestors. They use paper cut outs as an integral part of healing ceremonies, rituals, prayers, petitions, chants and dances, as these figures represent the different divinities/ gods, each having a specific power.

These cut papers of the divinities and supernatural forces were one of the most important tools used in Otomi rituals, and among the most ancient. From folded paper, a series of 40 “munecos” (8 x 5) are cut and laid on the floor. Copal incense is wafted over them; candles are lit, prayers of petition are chanted and called out. The cut-out deities begin to take on power. At the end of the ceremony, the paper cut outs are taken to the foothills to await the reply of the gods, hoping the petitions are heard and answered. Eventually, the paper will perish/disintegrate, taking the illness, maladies along with it.

From Cut Paper to Embroidered Cloth

Why do we mention the spirits and the tradition of cut out figures from Amate paper in the context of colorful embroideries?

According to Vazquez, these cut papers, used in healing rituals by the Otomi, “informed” and influenced the dibujos or drawings of the Otomi embroidered Tenangos. While the designs LOOK different, the meaning and symbolism behind them, (in them) come from the same place.

Both the curandero and the dibujante, perpetuate the history of their communities, their pueblos. Beings that have inhabited their world, mythical and real, the “perro”, “venado”, “jaguar” specific birds, such as vultures, eagles, doves, roosters, turkeys all symbols or messengers with specific characteristics float in harmony on the Tenango embroideries.

Finally, what Vazquez concludes, “While the curanderos may have disappeared or gone underground, their visions, messages, petitions remain alive in the bordados of the tenangos. It is they, the dibujantes, who preserve the symbolic world of the curanderos of San Pablo el Grande and San Nicolas. It is now, up to each one of us, knowing something about its history, meanings and symbols, to care for this legacy of the Otomi communities.”

For this reason, we believe it is important to know what is “behind” a cloth, embedded in its motifs and designs; where and who made them. Travel helps inform this, and deeper learning does too. For this reason, Tenango designs are not just pretty images to print digitally onto everything from dishes to fabric, or to copy in a “maquila” industrial setting. These images are the inheritance and living heritage of the Otomi people. We look forward to a future visit to this region.