Background

Laca or maque, lacquerware is an ancient technique and art form in Mexico. Laca, from the Persian term lak, (evolved to shellac), and maque, from the Japanese term, maki-e, and from the Arab word “sumac”, is a functional and decorative art, developed to create a protective coating or veneer over a surface, making it impermeable and beautiful. Using a combination of natural waxes, oils, minerals and pigments, a very durable and shiny coating is produced to protect and embellish objects. In its earliest application in Mesoamerica, guajes/bules (gourds), tecomates and jicaras (recipients for beverages and other uses) were used; later, with global trade and influences coming from Asia and Europe, items such as bateas (wooden trays), biombos (screens), writing desks and other decorative items were introduced.

Lacquerware is a very old art form that developed in Asia (very early in China and Japan), as well as in pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica, where lacquer was produced from the fatty extract of the llaveria-axin (commonly called “aje”), chia oil, minerals and pigments, to create a protective coating and to embellish dried gourds for drinking cacao, and other ceremonial uses.

Pre-Hispanic Times

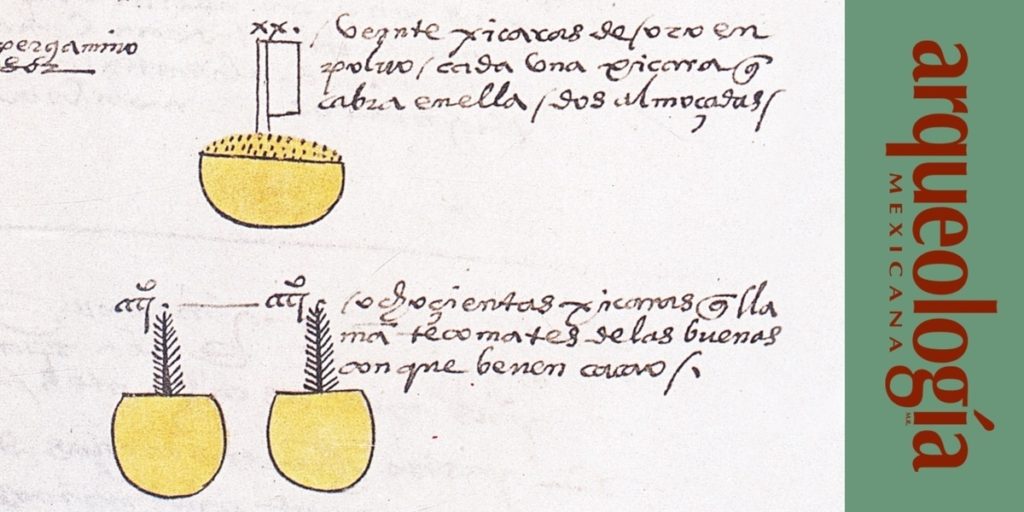

References to pre-Hispanic lacquer, came primarily from colonial texts and documents. The Matricula de Tributos from the Codex Mendoza shows pictorial references of decorated jicaras.

Early Spanish chroniclers such as Fray Bernardino Sahagun in his Historia General de las Cosas de España, mentions, “xícaras ricas”, “un vaso muy pintado hecho de calabaza”, “de colores muy finos y tan asentados, que aunque estén cien años en el agua nunca la pintura se les borra”.

And, in describing the Tlatleloco market, “para venderlas bien primero las unta con cosas que las hacen pulidas y algunas las bruñe con algún betún que las hace relucientes y algunas las pinta, rayando o raspando bien lo que no está lleno ni liso. Y para que parezcan galanas, úntalas con el axin o con los cuescos de los zapotes amarillas.” Bernal Diaz de Castillo mentions, “jicaras se usaban para lavar las manos, pintadas con ricas pinturas”. Fray Diego Duran makes reference to “tributaban xícaras doradas y pintadas ricas y curiosas pinturas, que hasta hoy en día duran y las hay muy curiosamente labradas, en fin todo género de estas xicaras grandes, medianas y chicas de diferentes hechuras y colores”.

But actual archaeological evidence was not found, until fragments from dry caves, burials and cenotes (Chichen-Itza) were discovered. In dry caves in the northern states of Coahuila, Sinaloa, Chihuahua and in the southern state of Chiapas, fragments of jicaras with evidence of maque were found.

Colonial Times

During the Colonial Period, maque became a very desired decorative art, combining pre-Hispanic materials and methods with European styles and Asian motifs and iconography. As with other decorative and textile arts of Mexico, such as talavera tile and the Mexican rebozo, a fascinating global fusion took place.

The Manila Galleon trade connected Asia, the Americas and Europe, bringing together Asian design influences such as, carving, black backgrounds, gold leaf, mother of pearl inlay, painted scenes of local villages, flowers, birds and other visual imagery. And, from the other side, European influences brought furniture, writing desks, and other items into this decorative art form in colonial Mexico. Asian aesthetics, European furniture styles, and pre-Hispanic techniques came together, resulting in new, beautiful and highly prized objects in New Spain. In fact, Europeans highly valued lacquerware produced in and imported from New Spain.

Today

Today, maque is found in three Mexican states: Michoacan, Guerrero and Chiapas. Following is some information I learned while visiting the Purepecha Plateau in Michoacan and the Mountain Region of Guerrero.

Uruapan and Periban, Michoacan

My first encounter with maque was at a Noche de Muertos Concurso in Patzcuaro. Browsing the halls of the former Jesuit school, a charming, small plate caught my eye. At first I thought it was a nicely painted wooden plate. But when I asked the informative staff of the Instituto del Artesano Michoacano, they told me it was maque.

Through Patricia Terán Escobar, Director, Museo de Artes e Industrias Populares de Pátzcuaro, I met Juan Valencia Villagomez, a great master of this art. Contacting Juan, he happily agreed to receive a group of travelers to visit his taller/workshop. What we learned there made us realize that the platter I bought was not painted. Rather, it was a complex technique that involved layering of greases, oils, minerals and pigments. Intricate decorating, carving and inlay processes, using natural elements, such as the fatty extract from an insect, oil from a seed, pulverized dolomite stone and natural pigments for colorants were involved. Everyone was amazed and delighted to observe and learn about maque from Juan and his group of accomplished students.

Materials and Procceses

In Michoacan, they combine the fatty extract of the “aje”, the llaveia axin insect, with chia oil. This mixture called “sisa” provides the adhesion, shine and drying properties. The artisan takes a smooth surface, such as a wooden batea and begins to apply a layer of sisa with their fingertips, rubbing it in with their palm. Next, a layer of pulverized rock, called teputzuta, or dolomite, (a mineral of calcium magnesium carbonate) is applied with a cotton ball, and is rubbed in until the powder is absorbed and the surface is smooth and uniform. This pulverized stone provides the resistance and durability. The layering of sisa and pulverized rock continues, until about 15-20 layers have been applied, achieving a desired thickness (a very thin layer/veneer).

Once the artisan has achieved a desired thickness and uniformity, and the piece has fully dried and “set”, the design is etched into the maque surface (free hand or with tracing paper). Once the overall design is completed, creating the cavities is next. The spaces are carved out, removing the layers of maque, until the base of the wood is reached. The spaces are then filled in with colored maque, colors that often (but not always) use natural pigments, such as cochineal, indigo, cempasuchil/marigold and others. This inlay technique is called “incrustado” or “embutido”. Each color has to be done at the same time before a subsequent color can be applied. Darker colors first, lighter colors at the end. For example, all the green leaf sections are filled in, and left to dry. Then all the red petals are filled in, and left to dry; yellows are the last color! Given that the drying of each section is time consuming, an artisan will have several pieces in process at any given time. Finally, the entire piece is polished and smoothed with chia oil, leaving a beautiful patina. The surface is completely smooth, but now we know it’s not painted!

Olinala, Guerrero and Surrounding Communities

My second and transformational encounter with laca was in Guerrero. I came across a mention of the Gran Concurso in Olinala, and I thought, “that’s the town known for the “cajitas” de Olinala!” This sounded amazing to me, knowing these boxes are such an iconic craft in Mexico. Highly motivated, I contacted the Ayuntamiento de Olinala for information. How do I get there? Where do I get the bus? How many hours does it take? A very kind and patient person said to me, “contact Bernardo, he’ll help you!” He readily gave me Bernardo’s number and I immediately called. “Hola Bernardo, mi nombre es Stephanie, el Ayuntamiento recomendó que hablara con usted, sobre el Concurso de Olinalá”. “Por supuesto”, said Bernardo. Hearing my enthusiasm, he invited me to join a caravan departing from Mexico City, instructing me to meet his niece in the south of the city. Arriving in Mexico City, I awoke early the next day, excited and to be at the meeting point on time. Meeting up with fellow travelers and everyone in tow, we embarked on an amazing journey. Little did we know, we’d be on a full day’s road trip, making interesting stops along the way. First, a delicious breakfast of tasajo; then to an ancient Olmec site, where we were reminded that the Olmec, in addition to settling on the Gulf Coast of Mexico, also settled in Guerrero. Our last stop was at a balneario to cool off in refreshing spring fed waters, and to enjoy a cold beer. Then, leaving the main roads, we navigated through stunning mountain ranges, valleys and meandering rivers. As the sun was just beginning to set, there was a golden cast to our panorama. At last, arriving in Olinala, we checked into the hotel and anxiously awaited for what was in store the next day.

After breakfast, our group toured and learned about the work of ICATEGRO (Instituto de Capacitacion Para el Trabajo del Estado de Guerrero), a vocational training school, under the Federal entity: SEP (Secretaria de Educacion Publica). One of nine ICAT training schools in Guerrero, ICAT Olinala was established in 2009, founded with the clear and singular mission to revive, preserve and train future generations in the ancestral art of the “laqueado” of Olinala and surrounding communities. Their mission is to teach, apply and maintain rigorous quality standards to the art of lacquerware, including materials and processes, creating national and international markets for their time valued art. Economic sustainability from highly valued and remunerated art, contributes greatly to the wellbeing of current and future generations in the region, stemming the tide of migration.

School Director, Bernardo Rosendo Ponce, (yes, that’s Bernardo!) led us on a tour to see the training rooms, workshops, showrooms, gardens, meeting halls of the school. Then, we learned about and observed each process, step by step, of the laca art of Olinala.

There are two primary styles/techniques of laca in Guerrero, (and a third hybrid style). The more intricate one is called “rayado” or “rayado vaciado”, meaning etched (scored) or etched and carved out. Unlike the Michoacan “incrustado” style where the cavity is filled in, inlay style, creating a smooth surface, the rayado style is the opposite. The carving is not to create a cavity, but to undercut the areas surrounding the design element, leaving the design raised; a bas-relief.

The second style in Olinala is called decorado or dorado. The interchangeability of the terms “decorado” and “dorado” can be confusing, but from the observation of Gutierre Tibon, who documented Olinala in the 1960’s, he tells us, “En las lacas de Olinalá, sustituyen a los filetes de oro, de la tradición antigua, uso de pintura amarilla. El uso copioso del oro que se hizo antaño, se manifiesta en el verbo dorar, que en el lenguaje olinalteco significa, simplemente decorar.” What was once done with gold, was later done with golden colored paint, hence the transition from dorado to decorado.

The decorado style does not have an etched/scored surface. Painting is applied to decorate the surface. Rayado punteado (etched and dotted) is a style that combines the bas-relief with the lower regions painted in a pointillist style; many dots. This is a hybrid style.

The maque process is similar to that of Michoacan, but not exactly the same. Each region finds their best and optimal technical and artistic “solution”. Much like a chef or cook might find a different approach to a recipe. This is often a function of the availability of / accessibility to raw materials.

Some unique aspects of Guerrero’s use of materials and techniques include: a.) They do not use “aje”. According to Rogelio Andrew Sanchez, Director of Operations at ICAT, he says that due to multiple environmental and social factors, aje has not been used in this region for over 50 years. They use another approach that combines chia oil with a siltstone, b). unique to Olinala is the use of the linaloe tree. Using an ancient method of notching the linaloe tree trunk with an axe, the sap concentrates in small areas, giving the wood and the wooden boxes their famous essence of linaloe. Today, not all boxes are made from this prized wood, so many artisans use an essence of linaloe to coat the inside of the boxes for the desired aroma. To see if your box is made from linaloe wood, you will notice a brown “stain”, darker wood area on the wood inside the box. This is where the linaloe tree was notched in the ancient method described above. c.) Guerrero uses a unique combination of three minerals, each having a specific property.

In Guerrero, they use three minerals, each having a different property and/or color. The tecostle (an iron oxide or siltstone) is a natural adhesive; the dolomite rock, called tóctetl, when pulverized to a fine talc, provides volume. When the artisan has his/her object ready for the maque process, this is what they do:

So, when in Guerrero, remember the three “Ts” tecostle, tóctel and tezicaltétl and you’re good to go! And, now you speak nahuatl, as these are all nahuatl words.

Surrounding Communities

In addition to Olinala, the surrounding communities of Temalacatzingo, San Martin Tecorrales, Ahuacatlan are also dedicated to laca art. In Temalacatzingo, they are most known for their toys, ferris wheels, swing sets, see-saws and other charming items. They are also known for their beautiful guajes, bules, jicaras. There are numerous initiatives taking place in and amongst these communities, to help future generations learn the art of the maque, so they have monetary rewards and incentives to maintain their art and to derive a livelihood from it.

Biodiversity and Cultural Expression

Renowned ethno-biologist and explorer, Wade Davis once said, “Cultural diversity is as important to our planet and survival, as is biodiversity”. In fact, biology, nature and culture go hand in hand. As with the caracol purpura on the Coast of Oaxaca, the cochineal bug in the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, the indigo plants in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, bugs, plants, minerals and many other elements of nature have been used in art, craft, textiles, and form a part of cultural identity.

Llaveia axin axin (aje)

In the case of maque in Mexico, a bug from the scale family has been important in the history of this art form.

Found in the warm tropical lowlands of the rio balsas basin, the Llaveia axin axin, is a member of the Coccus species, a type of scale insect. It is sometimes confused with the cochineal bug, which is also scale insect, but it’s from a different genus.

“The bug is processed for its fat content and is used as a lacquer coating on wood products, especially art and sculpture creations; this handcraft technique is known as “maque”. The fat resembles a soft wax that is a combination of free fatty acids and triacylglycerols; when rubbed onto the substrate, with various pigments it polymerizes into a durable and decorative film (sensuMac Vean, 2008). In Mexico several towns have historically specialized in this form of artwork. Among these places are Chiapa de Corzo (Chiapas State), Olinalá (Guerrero State), Uruapán and Pátzcuaro (Michoacán State).”

“The cultural impact of insects must not be neglected. We need to record the many uses of insects soon, before it is too late, as habits change and traditions are lost, information on the role(s) of insects in human cultures and societies will ultimately become irrevocable” (sensuSchabel, 2008).

I’m glad I stopped at that very first piece of maque I saw in Michoacan, several years ago. Visiting these maque art production centers in Michoacan and Guerrero, has opened my eyes, giving me a deep appreciation, admiration and wonder for this art form and the artisans who create it. It has a long trajectory and legacy, and we look forward to sharing this beautiful and complex art form with others, and to being a small part / cog in the wheel contributing to its preservation.

Our special thanks to:

Juan Valencia Villalobos, Master Artisan, Uruapan/Periban, Michoacan

Bernardo Rosendo Ponce, Director, ICATEGRO, Olinala, Guerrero

Rogelio Andrew Sánchez, Director of Operations, ICATEGRO, Olinala, Guerrero

The artisans of Periban and Uruapan

The artisans of Olinala, San Martin Tecorrales, Temalacatzingo

Suggested Bibliography

El Maque: Lacas de Michoacan, Guerrero y Chiapas, Artes de Mexico, 1972

Lacas: Color y Brillo Novohispano, Museo Nacional del Virreinato, 2017

Lacas Mexicanas, Coleccion Uso y Estilo, Museo Franz Mayer & Artes de Mexico, 2003

Marco Antonio Acosta Ruiz, ” El Maque de Michoacan: Su Historia y Produccion en la Actualidad”, 2013

Patricia Eugenia Acuna Castrellon, ” El Maque o Laca Mexicana: La Preservacionde una Tracicion Centenaria”, 2012

Recommended by ICATEGRO, Olinala

Carlos Espejel, “Olinala”, Museo Nacional de Artes e Industrias Populares, 1976

Gutierre Tibon, “Olinala”, 1960

Lourdes Hernandez Beltran, “El Arte de Olinala”, 2017

Notes:

I could write more, but instead, see a video here, #3 in a series of 3 videos produced by ICATEGRO. Enjoy!

Learn and Experience More: