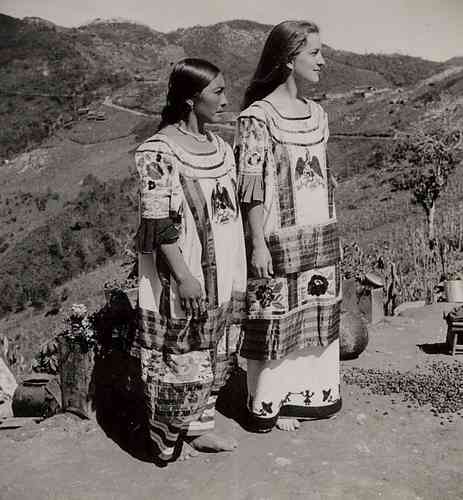

Irmgard in Huautla de Jimenez, Mazateca Alta, Photo: Irmgard Weitlaner Johnson, Collection, Biblioteca Juan de Córdova

Photo by Guy StresserPéan, Irmgard W. Johnson Collection, Biblioteca Juan de Córdova

Born in Philadelphia in 1914 to Austrian parents, Irmgard arrived to Mexico in 1922 at the age of eight. Her father Robert, a metallurgist, had a keen personal interest in studying native languages and cultures of the Americas. He moved the family to Mexico, where he began his ethnographic and linguistic studies of Mexico’s indigenous people. From an early age, Irmgard accompanied her father on weekends and holidays into the Nahua, Otomi communities surrounding Mexico City. Her longer expeditions began in 1934/1935, taking her to Mexico’s Chinantec region of Oaxaca. Led by anthropologist / linguist Bernard Bevan, and with her father, she ventured into remote regions of “La Chinantla” on expeditions that would shape her life.

Chinantla region of Oaxaca in Turquoise

En route to San Felipe Usila

Aided by a local guide from the Chinantec community of Chiltepec, the team bushwhacked through dense rain forests, cloud enshrowded mountains, green valleys, travelling by foot, horseback and mule. Arriving in villages, they would meet with local authorities to explain their intentions to study the Chinantec culture and language and to seek assistance obtaining food and shelter. “In the villages and ranches it was difficult to find food, because the people had little to offer. For this reason, the team took provisions, namely corn, they had ground to make tortillas.” Kirsten Johnson Saberes Enlazados

“Chalupa” canoe on the Rio Usila

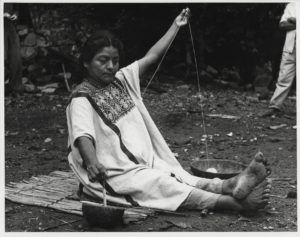

Woman spinning cotton in Valle Nacional, Photo: Irmgard W. Johnson, Biblioteca Juan de Córdova

According to Kirsten, Irmgard’s daughter, her mother witnessed a massive shift in textiles during the period from 1935 to 1975, where indigenous methods, use of materials and processes for internal consumption and local trade gave way to industrial materials, processes for an external market for textiles. Commercial threads (cottons and synthetics), dyes, and the tourist market became significant factors resulting in major shifts in the material culture and economy of indigenous communities throughout Mexico. Clothing was no longer solely a cultural expression, but also became a commercial commodity. Irmgard observed these changes and in some cases extinction, for over 40 years.

This radical transformation, compelled Irmgard to meticulously document and collect what she saw, in an effort to preserve. Upon completion of her studies in cultural anthropology and ethnographic textiles at UC Berkeley, she began her systematic work in 1951. With the support of various cultural institutions, including the National Museum of Anthropology, where she later was curator of textiles, she amassed a collection of Mexico’s ethnographic textiles. She also studied and documented weaving structures, took extensive field notes, photos, sketches from Zapotec, Chinantec, Mazatec, Cuicatec, Triqui, Mixtec, Mixe communities in Oaxaca; Tzotzil, Tzeltal, Zoque in Chiapas; Nahua and Otomie in Hidalgo; Totonac, Tepehua, Otomie, Nahua in Puebla; Maya of Yucatan, Raramuri of Chihuahua, Otomie and Mazahua of the State of Mexico. Kirsten Johnson, Saberes Enlazados

Perhaps the biggest change she observed was the use and processing of fibers, such as plant fibers from agave, yucca, others, and hand spun cotton and native silk, giving way to commercial cottons and synthetic fibers. And, natural dye sources such as cochineal, indigo and others, began to be replaced with synthetic dyes.

Shifts were also seen from brocade woven designs (supplementary weft) to embroidered designs, as well as the use of commercial white cloth, such as muslin, versus hand-woven white cloth in plain and gauze weave. It was observed by Johnson that the weave structure of plain gauze provided a perfect template for embroidery, particularly cross stitch. Today, this white gauze weave base cloth is often replaced with a commercial substitute called “quadrille”, a store bought fabric that mimics a gauze weave layout for ease of use when counting / laying out cross stitch embroidered patterns.

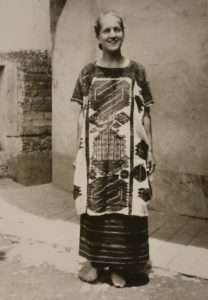

No place fascinated Irmgard more than La Chinantla, a remote region of Oaxaca between the eastern slopes of the Sierra Juarez mountains and Veracruz on the Gulf of Mexico. Here, she took copious notes on weaving techniques and design motifs. “For the rest of her life, the handwoven dress of la Chinantla became Irmgard’s source of inspiration and happiness for Irmgard, a place she would return to on numerous occasions to document”, Kirsten Johnson, Saberes Enlazados

Irmgard wearing huipil “diario” from San Lucas Ojitlan. Photo in Collection at Biblioteca Juan de Córdova

Couple in San Felipe Usila, 2012, courtesy Kirsten Johnson

Irmgard observed and documented changes in La Chinantla. Returning in 1952, she reported that access to the region had improved, making it less isolated; some elderly women were still wearing traditional huipiles, yet few knew how to weave them. She observed more embroidery and less brocade weave for the web panels of the huipiles, and commercial cotton was predominantly used. She did find that the deeper she traveled into more remote regions of La Chinantla, weavers were still hand spinning cotton, but were combining it with the industrial variant. And, as she was there during Holy Week, she observed that many of the finest “fiesta” huipiles were worn for the occasion; these being the lovely hand spun gauze weave with supplementary weft / brocade designs she had seen on earlier trips. She observed great fusions of materials, designs, embellishments and communities wearing each other’s huipil designs.

Her daughter Kirsten reports going to La Chinantla in 2012, returning to a place she had not been to since she was twelve! Kirsten says this visit was a shock to her, as so much had changed and the loss of dress was so apparent in communities such as San Felipe Usila, Valle Nacional, Chiltepec.

Change and evolution are inevitable. Some change is externally induced and some is internal, coming from the communities themselves. Tastes in style, fashion, expression change and evolve everywhere. Today, the Usileñas for example, love to embellish their huipiles with satin ribbons, lace and rickrack. On this huipil, more is more, including density of weave and color!

Photo taken by Irmgard W. Johnson, Easter, 1952. Photo courtesy of Kirsten Johnson

Woman in San Felipe Usila, 2013, Photo: Stephanie Schneiderman

I had the great honor of meeting Irmgard in 2009 in Mexico City. It was a brief meeting, but one I wont forget. There are people you meet in life who leave an impression and have an impact on you; Irmgard was one of them. She said, “You’ll know your passion, and follow it”. This was a woman of clarity and conviction. It is no wonder she left such a mark on the world of ethnographic textile studies in Mexico and on the people who knew her.

We invite you to join us in June during the WARP Annual Meeting in Oaxaca, where we will offer a Pre-Tour of La Chinantla, to continue observations of the region begun by Irmgard W. Johnson. One community, Rancho Grande, Valle Nacional has embarked on a revival initiative to include the teaching of plain and gauze weave and most recently, brocade weave (supplementary weft). Two of the elderly women of the community taught the next generation, who are teaching the next. We’ll visit them! Arriving in Oaxaca City, we’ll meet with Kirsten, Irmgard’s daughter, to learn more about her pioneering mother. We’ll travel again to the region in April 2017 on an extended Textile Journey to Veracruz, La Chinantla and Tlaxcala. We hope you can join us. We invite you to read further: Saberes Enlazados, by Kirsten Johnson, source for this post.

Brocade woven center panel, embroidered side panels over woven cloth, huipil from Rancho Grande, Valle Nacional, 2013

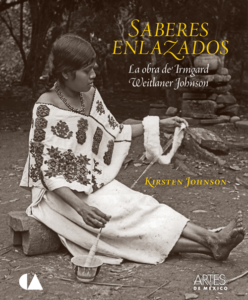

Saberes Enlazados, The Work of Irmgard Weitlaner Johnson, by Kirsten Johnson

See our Photo Gallery Here: Enter la Chinantla!

1 Comment

Pingback: Weitlaner Johnson: Pioneer, ethnographic textiles studies of Mexico | Creative Hands of Mexico